Advanced stress testing for DevOps

Last Updated on December 27, 2025 by David Both

A little over a year ago, I found an interesting tool, stress, that allows SysAdmins to perform some stress testing of Linux systems. It’s a great little utility that provides some basic tests for disk, I/O, memory, and CPU. It provides configurable load amounts and a timing function. But it is rather simple and hasn’t been updated in a couple years.

stress-ng

I recently discovered stress-ng which, while similar to the original stress program, is a completely new tool that offers far more flexibility and granularity in testing while keeping the basic command syntax. In addition to basic stress testing, it also has a wide range of CPU tests that can be used to target specific functions such as floating point, integer, bit manipulation, cache, vector instructions and control flow. This incarnation of the utility also provides stressors for maths in the form of hash, Bessel and other functions; as well as file handle operations, text, timer, binary search, bubble sort, and heapsort stressors among many others.

stress-ng also has a GPU stressor that I wanted to try but the kernel on my Fedora installation wasn’t built with the required supporting functionality. The good news is that the error message tells you exactly what’s missing. If you have the knowledge, you can recompile the kernel to include those functions.

The stress-ng utility is not installed on Fedora by default so I had to install it myself. It’s available from the Fedora repository, so that makes it easy. It’s also in the Ubuntu and Linux Mint repos.

# dnf -y install stress-ngBasic usage

I like to view what’s taking place inside my test computers while running stress tests. There are plenty of options for this, but my favorites are btop, htop, and sometimes iotop.

I’ve been working to convince myself that the BtrFS filesystem is stable and resilient enough that I might use it in my own systems. I’ve been using the stress-ng tool for that and it’s given me good information about my test system with only the filesystem in question under test as well as additional testing with some or all of the other system components uder stress, such as memory, CPU, I/O, DIsk, and more.

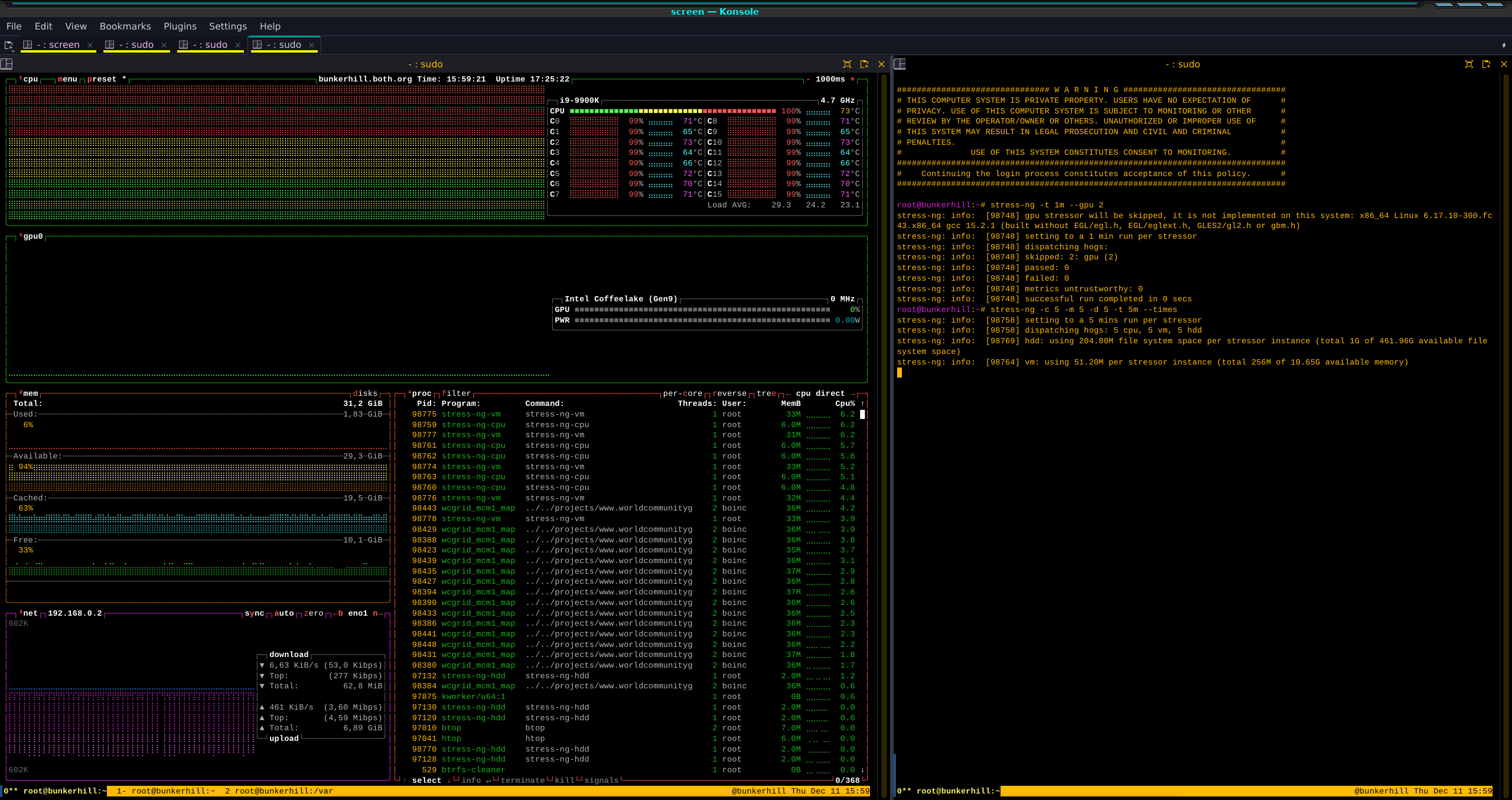

I usually start btop and htop on the left terminal of a vertically-split screen session in one tab of the highly flexible and configurable Konsole terminal emulator. In the right terminal, I start the stress-ng utility with whatever set of stressors I want for the current test. Figure 1 shows this setup in one of my early tests much more clearly than words can.

You can click on Figure 1 to enlarge it for a better view, to see two of the commands I used in the right panel to test both the BtrFS filesystem as well as the rest of the system. I spent several hours testing with different combinations of stressors as well as different time-frames from a few minutes to five days. The hardware I’m testing is a mid-range system that’s about 6 years old with the specifications in Figure 2.

#######################################################################

# MOTD for Sat Dec 13 03:30:03 AM EST 2025

# HOST NAME: bunkerhill.both.org

# Machine Type: physical machine.

# Host architecture: X86_64

#----------------------------------------------------------------------

# System Serial No.: Default string

# System UUID: 3b702977-a782-a01e-a08f-2cf05d26c209

# Motherboard Mfr: Micro-Star International Co., Ltd.

# Motherboard Model: Z390-A PRO (MS-7B98)

# Motherboard Serial: K316882609

# BIOS Release Date: 12/25/2019

#----------------------------------------------------------------------

# CPU Model: Intel(R) Core(TM) i9-9900K CPU @ 3.60GHz

# CPU Data: 1 Eight Core package with 16 CPUs

# CPU Architecture: x86_64

# HyperThreading: Yes

# Max CPU MHz: 5000.0000

# Current CPU MHz: 4700.009

# Min CPU MHz: 800.0000

#----------------------------------------------------------------------

# RAM: 31.210 GB

# SWAP: 7.999 GB

#----------------------------------------------------------------------

# Install Date: Wed 22 Oct 2025 11:50:12 PM EDT

# Linux Distribution: Fedora 43 (Forty Three) X86_64

# Kernel Version: 6.17.10-300.fc43.x86_64

#----------------------------------------------------------------------

# Disk Partition Info

# Filesystem Size Used Avail Use% Mounted on

# /dev/nvme0n1p3 475G 20G 452G 5% /

# /dev/nvme0n1p3 475G 20G 452G 5% /home

# /dev/nvme0n1p2 2.0G 590M 1.3G 33% /boot

# /dev/mapper/vg02-Pictures 466G 104G 362G 23% /var/Pictures

#----------------------------------------------------------------------

# LVM Physical Volume Info

# PV VG Fmt Attr PSize PFree

# /dev/sda vg02 lvm2 a-- <465.76g 56.00m

#######################################################################Figure 2: The specs for my test system.

Figure 3 shows an example of one of my more complex tests with a short duration. In this case I used 5 CPU stressors, 5 memory stressors, and 5 disk stressors. The default storage device to be tested is the present working directory (PWD). Although I could have used some fancy options to test a storage device that’s not the PWD, I think this was sufficient for my purposes and the easiest to set up.

# stress-ng -c 5 -m 5 -d 5 -t 5m --times --keep-files --hdd-bytes 10G

stress-ng: info: [743040] setting to a 5 mins run per stressor

stress-ng: info: [743040] dispatching hogs: 5 cpu, 5 vm, 5 hdd

stress-ng: info: [743051] hdd: using 2G file system space per stressor instance (total 10G of 464.75G available file system space)

stress-ng: info: [743046] vm: using 51.20M per stressor instance (total 256M of 10.87G available memory)

stress-ng: info: [743058] vm: x86 movdiri instruction not supported, dropping back to plain 64 bit writes

stress-ng: info: [743040] for a 386.17s run time:

stress-ng: info: [743040] 6178.80s available CPU time

stress-ng: info: [743040] 2538.70s user time ( 41.09%)

stress-ng: info: [743040] 49.55s system time ( 0.80%)

stress-ng: info: [743040] 2588.25s total time ( 41.89%)

stress-ng: info: [743040] load average: 24.01 25.73 21.04

stress-ng: info: [743040] skipped: 0

stress-ng: info: [743040] passed: 15: cpu (5) vm (5) hdd (5)

stress-ng: info: [743040] failed: 0

stress-ng: info: [743040] metrics untrustworthy: 0

stress-ng: info: [743040] successful run completed in 6 mins, 26.17 secsFigure 3: A somewhat more advanced test using a short duration.

The new stress-ng command provides a better timeout option, which is the length of time the stressors will run. The original stress command only recognizes seconds, so required a bit of math. The stress-ng -t option recognizes seconds, minutes, hours, days or years with the suffixes s, m, h, d, or y. It also supports a long version of the option, --timeout.

The – – keep-files option tells the utility to not delete the files used for stress-testing the storage drives. They’ll remain between runs and all new files will be used for the next run. This is one way to fill the device during testing. The – – hdd-bytes 10G option defines 10 GB as the file size for disk testing.

I also like the – – times option. It displays the cumulative times and load averages for the CPUs after the stressors are all terminated, either by the timer or manually using Ctrl-C.

Advanced usage

The stress-ng utility provides a massive number of options that can allow Linux kernel, system tool, and application developers to target tests to meet specific requirements. For example, one test can create a directory tree to the maximum depth allowed by the PATH_MAX environment variable. Another test creates as many files in a directory as possible and then deletes them. Another creates as many directory entries as possible.

A decimal floating point stressor offers 12 methods for testing floating point operations, as well as an option to use them all. Many other CPU intensive stressors are available, as are network (datagram), mutex process exclusions, stressors that run in cycles, CPU affinity, virtual memory, trigonometric, cryptographic, page swapping, file copy, and a vast range of others.

It’s important to be aware of side-effects. It’s possible to cause dangerously high temperatures that could cause physical damage to the system hardware or, at the very least, cause the system to shut down.

And whatever you do, don’t under any circumstances use the – – ignite-cpu option which forces the CPU to run hot. Well, unless you are a tester in asituation where part of your job is to test what happens when a computer runs hot — very hot. You definitely don’t want to do this on your own systems. I mean, the option name should be worrisome enough.

My use cases

My primary use cases for any stress-testing software is to burn-in computers I’ve just built or repaired, either with new hardware or software. I also use it to test major changes such as migrating from the LVM/EXT4 filesystem to BtrFS.

For the most part, I don’t foresee myself using most of the advanced capabilities of stress-ng frequently or possibly ever. But I will definitely be using the more mundane tests quite frequently.

Final thoughts

The stress-ng utility provides testers, developers, and SysAdmins a powerful new open source tool for stress-testing Linux systems at all life stages. I’ve been using it extensively to test a system I’ve just converted to BtrFS so I can more fully understand the filesystem’s stability and robustness. This requires testing of many simultaneous stressors of CPU, memory, I/O, as well as the storage filesystems, under differing loads for each type.

Be sure to read the extensive 7000+ line man page for details of the many testing functions available. I was surprised at the number and depth of the available stressors. I’ve not seen a tool that provides better stress testing and is free open source (FOSS) as well. Because stress-ng is designed as a command line tool using STDIO it can easily be used in scripts for automated testing.

The stress-ng utility is for stress-testing only — it is not a tool that should be used for performance benchmarks.