My first Linux system

When I went to university in the early 1990s, I discovered our Unix computer lab. I immediately fell in love with the Unix command line, which was both somewhat familiar (due to my DOS experience) and powerful (because of all the commands that did things that DOS never imagined, especially with processing and manipulating text files.

It was with that context that I was so excited in 1993 to learn about this new thing called Linux, a free version of Unix that I could run on my ‘386 computer at home. I immediately wanted to try it out.

Softlanding Linux System (SLS)

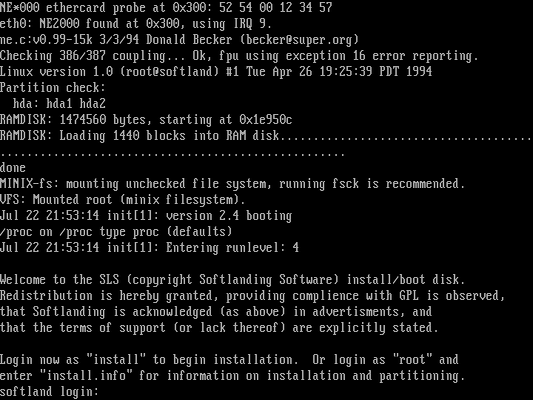

My first Linux distribution was Softlanding Linux System (SLS) 1.03, with Linux kernel 0.99 alpha patch level 11. My ‘386 had just enough horsepower that I could install and run Linux.

A year later, I upgraded to SLS 1.05, with the brand-new Linux kernel version 1.0, which introduced this new idea called kernel modules. With modules, you no longer needed to completely recompile your kernel to support new hardware; instead you just loaded a kernel module (there were 63 of them at the time). SLS 1.05 included this note about modules in the distribution’s README file:

Modularization of the kernel is aimed squarely at reducing, and eventually eliminating, the requirements for recompiling the kernel, either for changing/modifying device drivers or for dynamic access to infrequently required drivers. More importantly, perhaps, the efforts of individual working groups need no longer affect the development of the kernel proper. In fact, a binary release of the official kernel should now be possible.

On August 25, Linux turns 34 years old. To celebrate, I reinstalled SLS 1.05 to remind myself what it was like to run Linux for the first time, all those years ago.

Installing SLS

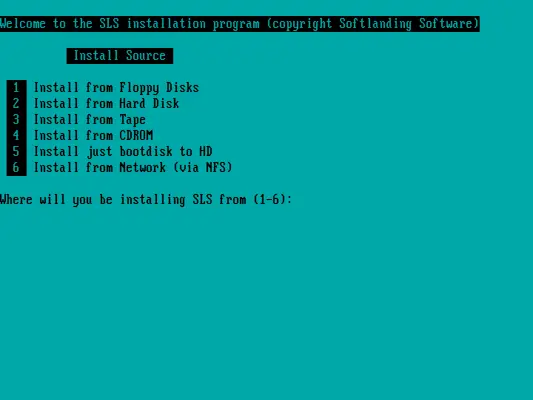

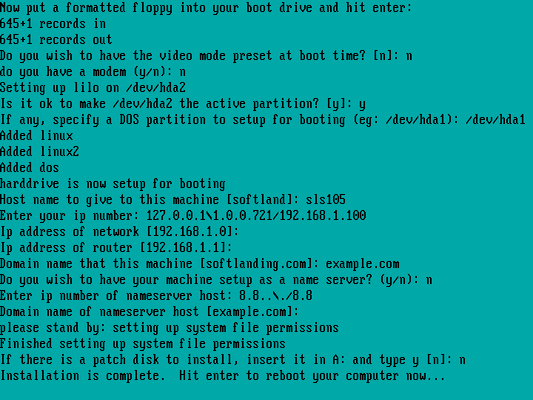

SLS was the first Linux distribution that you could call a distribution. Before then, if you wanted to install Linux on a new PC, you basically had to make an image of a working Linux system and copy that to the new computer. SLS provided an install program. To be fair, it was a very basic installer, but it did the job. To start, you boot the install floppy, then login as the install user.

A neat feature introduced in SLS 1.05 was the color-enabled text-mode installer. When I selected color mode, the installer switched to a light blue background with black text. This didn’t really offer much of an experience, but I guess it was better than the plain white-on-black text used in previous versions.

SLS was released in the 1990s, when distributions were provided on floppy disk. That’s how I installed SLS this time, from a stack of virtual floppy images. This was a bit of a pain to install in a virtual machine, because I had to swap out each of the floppy images in the virtual machine every time the installer asks for a different floppy, but eventually I got there.

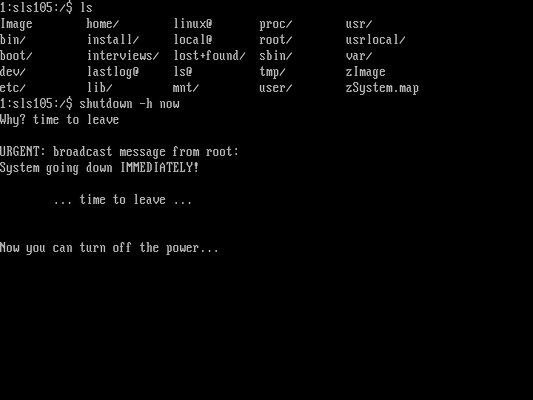

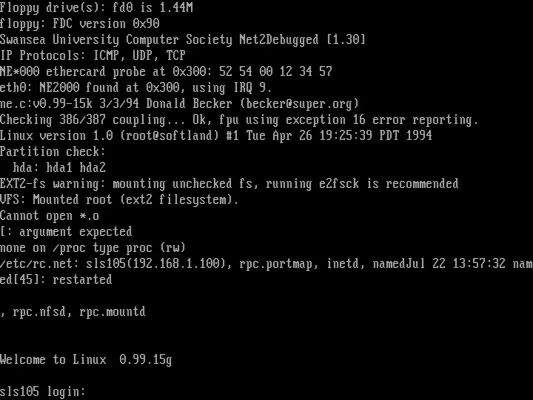

By responding to a few simple prompts, I was able to create a partition for Linux, put a filesystem on it, and install SLS. When I finished the install and booted into the SLS login prompt for the first time in so many years, I felt transported back in time.

Trying it out

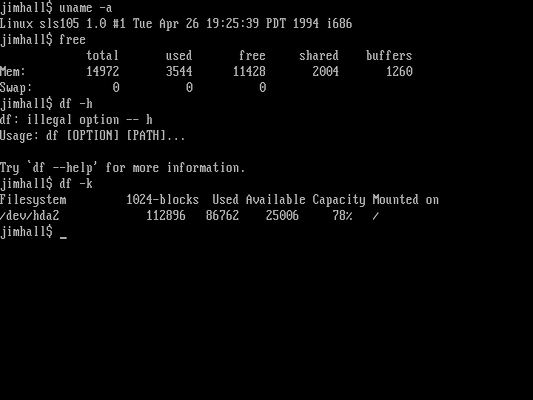

Let’s highlight a few things about this early Linux distribution. Linux 1.0 didn’t need a lot of overhead, requiring just 2 MB of RAM to boot, or 4 MB if you want to compile programs, or 8 MB to run the X Window System. And the distribution didn’t take much room, either. SLS 1.05, including the X Window System and development tools, used about 85 MB of disk space. That may not sound like much space by today’s standards, but when Linux 1.0 came out, 120 MB hard drives were still common.

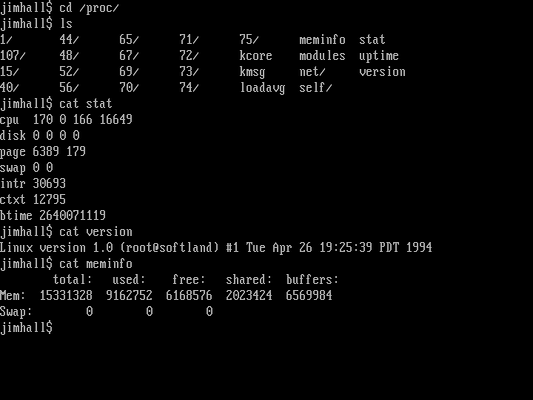

The familiar /proc meta filesystem exists in Linux 1.0, although it doesn’t provide much information compared to what you see in modern systems. In Linux 1.0, /proc includes interfaces to probe basic system statistics like meminfo and stat.

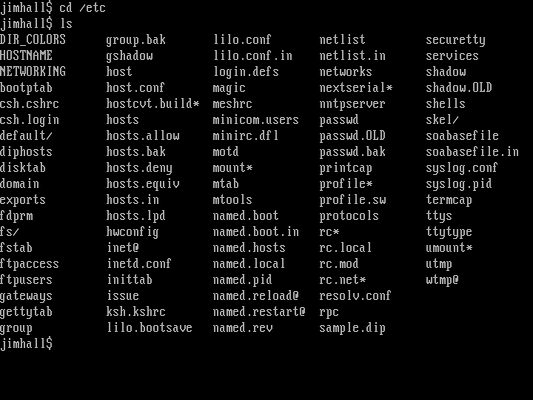

The /etc directory on this system is pretty bare. Notably, SLS 1.05 borrowed the rc concept where the system loads everything from rc scripts, with local system changes defined in the rc.local file. It was a simpler time when you could easily modify what got loaded just by editing a few files.

Back to work

With my system up and running, it was time to see what I could do with it. In the 1990s, SLS was pretty cutting edge. While my DOS system had many more “mature” applications like Lotus 1-2-3 and As-Easy-As for spreadsheets, WordPerfect and Galaxy Write for word processing, ProComm and Telix for dial-up access, and a host of other applications and games, Linux didn’t have a lot to offer at the time. But it had enough to show promise.

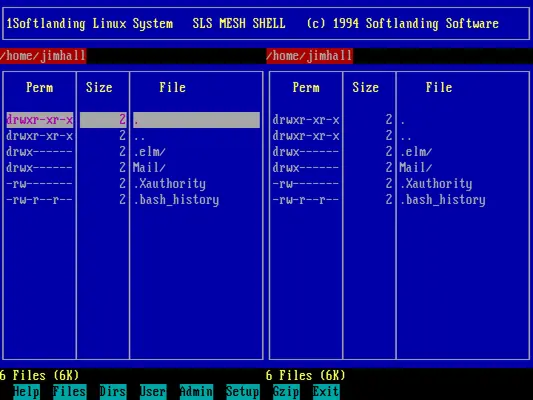

Let’s start with basic file management. SLS included Softlanding menu shell (MESH), a file-management program similar to Midnight Commander. Users in the 1990s might have compared MESH more closely to Norton Commander, a popular file manager available on MS-DOS.

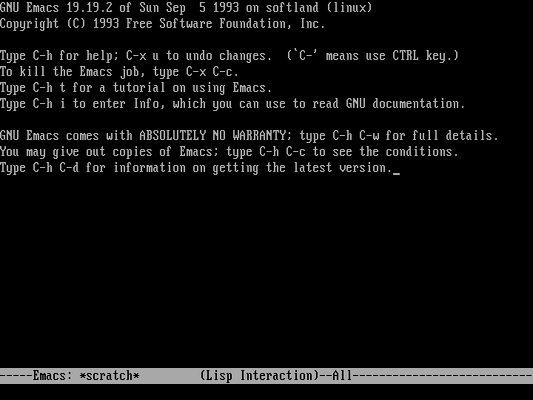

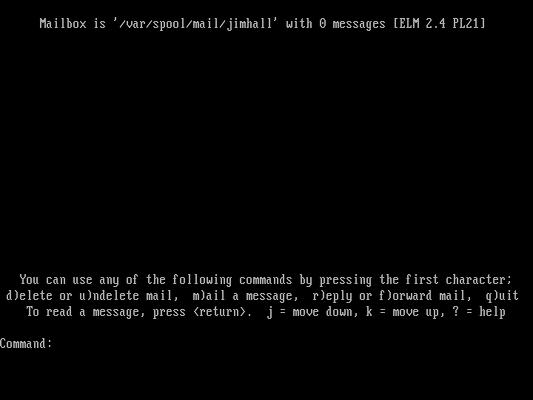

Aside from MESH, SLS included a few other full-screen applications, including ELM to read email, GNU Emacs, and the venerable Vim editor.

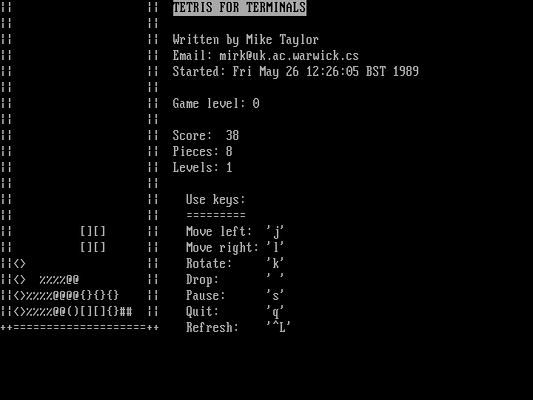

SLS also offered a few games, including a terminal-based version of Tetris. If you were alive in the 1990s, you didn’t have to go far to see a version of Tetris running somewhere.

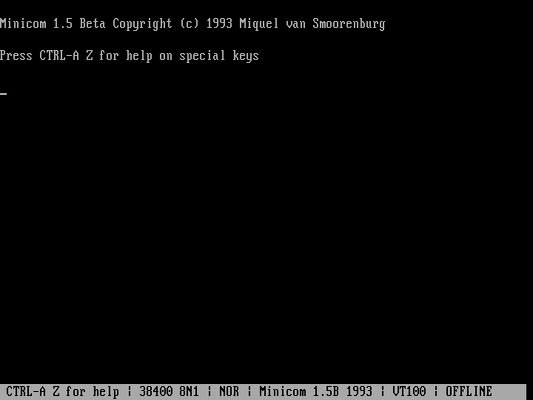

In the 1990s, home users were more likely to talk to the outside world over a modem. SLS 1.05 included the Minicom terminal application, which gave a direct connection to the modem, such as the AT commands to dial a number or hang up the line. Minicom also supported macros and other neat features to make it easier to connect to your local modem pool. As an undergraduate student in the 1990s, I used Minicom all the time to dial into the campus computer network.

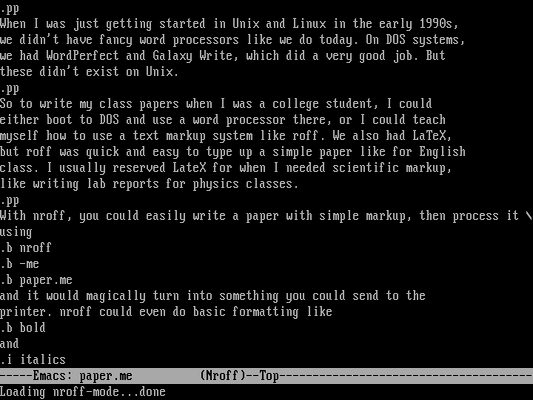

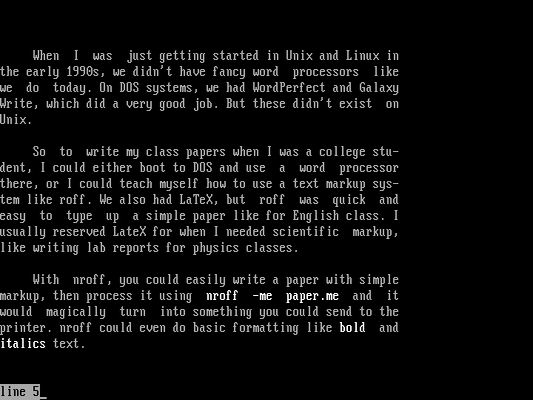

Unix systems didn’t have desktop word processors at the time. It would be years before StarOffice (the proprietary predecessor to OpenOffice, later LibreOffice) would be available for Linux systems. Instead, if you wanted to write a document, you used a document preparation system like LaTeX, nroff, or troff.

Actually, troff was for phototypesetters, but GNU provided the groff workalike since the late 1980s, which produced Postscript output. At the time, the typical way to print nice-looking groff output was to use GNU Ghostscript to convert and print it on my Epson dot matrix printer. But this was very slow and required a lot of printer ribbon to cover the several passes required for high resolution output on my 9-pin printer. Most of the time, I used the nroff processor instead, which used plain text that I could print anywhere very quickly.

As an undergraduate physics student, I also used LaTeX to write lab reports that required formatting equations; I would print LaTeX documents on my printer in the same way, with Ghostscript, although I would sometimes spend a few bucks to print it on the laser printer in the campus computer lab instead.

Running the X Window System

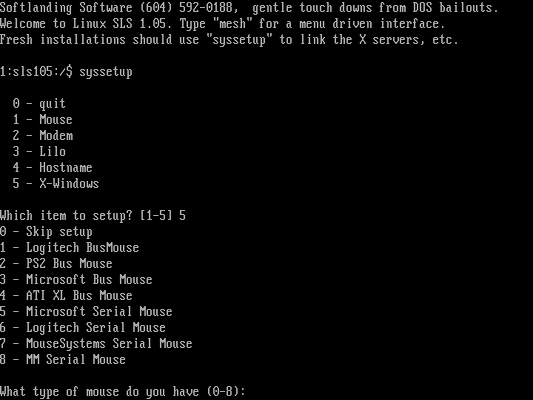

Configuring the X Window System by hand really can be a sobering experience. The X Window System could support a variety of video cards and monitors, and setting up the X Window System for the first time required a lot of experimenting with sync rates and resolutions until you settled on something that worked. SLS 1.05 made this a little less painless by providing a “helper” program to identify and define various system settings for you. After a few prompts, and some tweaking, I was finally able to launch the X Window System.

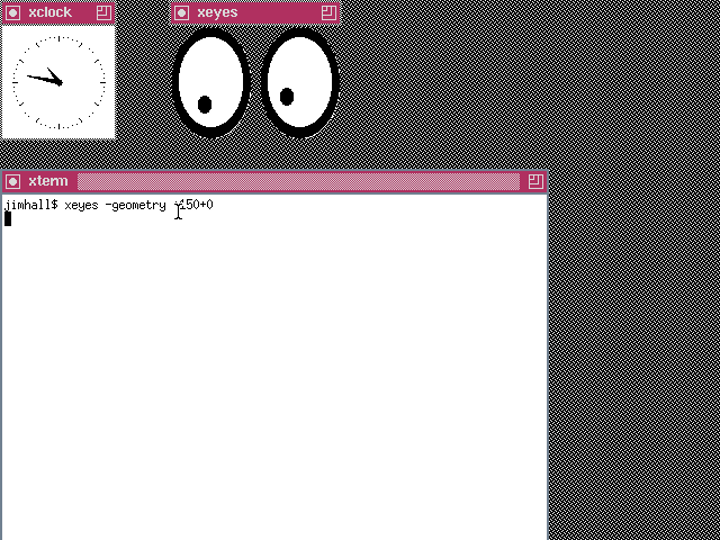

But this is from 1994, and the concept of a desktop didn’t exist yet; KDE wouldn’t arrive until 1996, and GNOME until 1999. In 1994, I used TWM until I was able to upgrade my home system, then I switched to FVWM. TWM is a simple, no-frills, functional, graphical environment—but it was also much easier to set up, so that’s what I used here.

A blast from the past

As much as I enjoyed exploring my Linux roots, eventually it was time to return to my modern desktop. I originally ran Linux on a 32-bit ‘386 computer with just 8 MB of memory and a 120 MB hard drive. That wasn’t bad for the era, but it’s very pokey compared to today. I should note that SLS runs much faster in a modern virtual machine, especially one that’s hosted on my dual-core, 64-bit Intel Core i5 CPU with 4 GB of memory and a 128 GB solid-state drive. You don’t really get to experience the delay of typing a big command before you see the output, or starting a build with make and watching the compiler slowly grind through all of the source files.

But running this original version of SLS served as a great reminder for how far we’ve come with Linux. Back in the 1990s, Linux was a great step forward for folks who ran Big Unix systems—but not much of a step up from more mainstream “desktop” operating systems like DOS or Mac. Today, Linux is more than a Unix replacement, it’s a modern desktop environment that’s easy to use and filled with apps. So while I enjoyed this look back at Linux from 1994, I was also glad to return to Linux in 2025.