Version Control Is Not Just for Code

Most editing problems are really problems of change management.

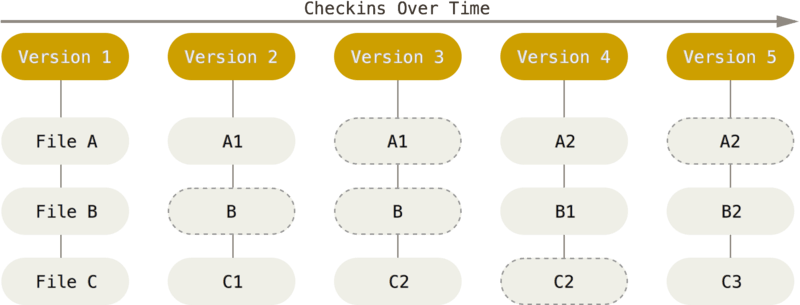

When multiple people are editing the same document, spreadsheet, or plan, things can get messy fast. Copies multiply. Feedback arrives out of order. Someone asks why a change was made, and no one is quite sure anymore. Over time, the fear of breaking something slows everything down.

That is why I use Git locally for non-code work.

I use version control on my own machine for articles, exam questions, planning documents, spreadsheets, and even things like DrupalCamp session selection. These files change frequently, often go through multiple revisions, and benefit from clear history. Git gives me that structure and, unexpectedly, a way to track how my thinking changes over time, all without a remote service or shared platform.

Initializing a local repository

Getting started is straightforward.

I create a directory for the work and initialize a local repository:

git initNothing leaves my machine. There is no remote. This is about tracking change, not publishing work.

The first file I add is usually a README. It explains what the folder contains, how files are organized, and what the work is for. Even when I am the only contributor, that context helps later.

git add README.md

git commit -m "Initial commit with context and structure"I also commit early. Folders for articles, spreadsheets, notes, or supporting material go in right away. That first snapshot becomes a clean baseline.

File organization that supports change

Text is kept in plain text whenever possible.

Markdown works well for articles, outlines, and documentation because it is readable and diffable. Exam content and policies benefit from being line based, which lets Git show exactly what changed between revisions.

Spreadsheets are less diff-friendly, but version control still helps. Even locally, Git tracks when a file changed and why. That alone is enough to prevent confusion about which version is current.

Consistent structure makes it easier to find things and understand changes over time.

Diff as the primary interface

Diffs let me see exactly what changed, without rereading everything.

I can review exactly what changed:

git diffThis is especially useful when I step away from a draft and come back later. I can immediately see what I changed last and pick up where I left off.

For committed changes, history stays visible:

git log

git showThis turns editing into something inspectable rather than fragile.

Commits as intent

I treat commit messages as a way to explain decisions. A commit message like:

git commit -m "Reword introduction for clarity"captures why a change happened, not just what changed. That context matters weeks or months later when revisiting work.

For things like collaborative articles or governance documents, commit history becomes a simple record of decisions. I do not need separate notes to remember why something shifted. The repository already tells the story.

Branches as private experimentation

Branches are how I experiment locally without pressure.

If I want to try a different structure for an article or test a new scoring approach for session selection, I create a branch:

git checkout -b try-new-structureNothing is at risk. The main branch stays stable. If the experiment works, I merge it. If not, I delete the branch and move on.

git checkout main

git merge try-new-structureBranches normalize exploration, even when working alone.

Collaboration still benefits

Even when Git is local, it still supports collaboration.

When I want to share work with others, I have a few simple options. I can send the entire repository as a ZIP or tar archive, preserving the full history. The recipient can unpack it and immediately see every change, commit message, and decision that led to the current version.

git archive --format=zip HEAD > project.zipIf someone only needs to review specific changes, I can share a patch instead. A patch is a small file that represents the difference between versions. It can be emailed, reviewed, and applied without sending the entire repository.

git format-patch -1For handoffs, I can copy the repository directly or place it on shared storage. Nothing special is required. Because the history lives with the files, context travels with the work.

This makes review easier. Changes are explicit. Decisions are visible. Nothing depends on memory, inboxes, or overwritten files.

Local-first Git keeps control with the person doing the work, while still making it easy to collaborate when needed.

This is editing infrastructure

Using Git locally for non-code work is not about tools or platforms. It is about building editing infrastructure that respects change.

Version control lowers anxiety, makes experimentation safer, and preserves context. It treats writing, planning, and organizing as work worth protecting.

Git is not just for code. It is for anyone managing change, even when that work is entirely on their own machine.